Ok, wow. Usually I start by introducing the game, but in this case, let me start by prefacing this post with the fact that this is undeniably the *worst* serious game I have had to cover. Ever. To make this clear, I am not exaggerating when I say I actually popped a vein when I played this – that really happened.

OK, so what game could possibly be responsible for this? Well, today’s offender goes to the game of SPARX, an award winning, and (as claimed repeatedly by its creators) clinically proven game to manage and treat depression. Joining me today will be Ronald, who usually hangs around when I play some of these serious games, but found the game so frustrating that he will be joining me tonight on this post, citing that this was the first time he was pulled from benign amusement into hostile detestment..

SPARX was built by researchers from the University of Auckland, consisting of Dr. Theresa Fleming, and: Associate Professor Sally Merry, Dr. Karolina Stasiak, Dr. Matt Shepherd, Dr. Mathijs Lucassen. This team, while impressively credentialed, has zero known experience with any game design, which definitely was not a good sign to start with. The game they built was designed to treat mild to moderate depression in kids and teens, through a culturally sensitive lens.

There’s just one, teensy, almost insignificant problem.

IT SUCKS

OK, now with that minor tidbit out of the way, let’s talk about the game experience. From the moment we started the game, we were accosted by a hilariously patronizing tutorial called “The Guide”. Now, I realize that the creators of this game have game design experience bordering on little to none, but a general rule of thumb is you have about 30 seconds to make your case to a potential user. We spent the first 10-15 minutes listening to the Guide ramble on aimlessly about what depression is, how SPARX can help, boring details that from my own experiences, would have any child turning the game off.

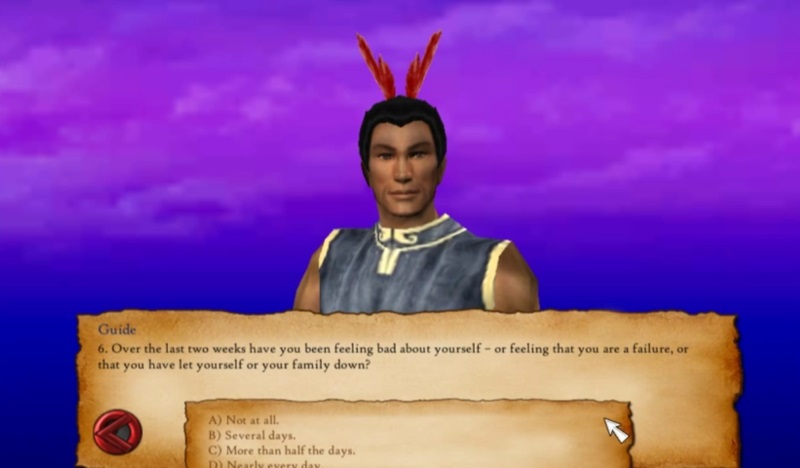

After the hilarious introduction, we then proceed to the section of the game which quizzes the player on their current state of mental health, which at this point, is probably likely deteriorating. This quiz has been lifted from a psychology textbook method of measuring depression in a clinical setting, with zero modifications made to account for the fact that this is a video game. As a result, the player has almost no motivation or desire to continue, since the game has still not even started – the player or child is being asked to perform a quiz before they’re even convinced that they want to play this game. Let me spell this out a little more clearly.

The vast majority of children will have left by now.

This is the key failing of SPARX – it acts it’s still in a clinical setting, and as such, that the user is compelled to complete whatever impositions are made on the user by the app, and as such, it continues to make increasingly outrageous demands on the user.

After, we have finally, finally finished the outrage that is the pre-game section, which took us about 15-20 minutes, we are finally allowed to play the “game”. This is where the truly atrocious part begins.

The first problem is the setting. The setting is…for lack of a better way to put this, extremely generic precursor fantasy that seems to mistake generic fantasy gear for actually legendary and compelling items and plot. Upon entering the game, the designers perform the novice mistake of attempting to introduce their world through a whirlwind of exposition – another 2 minutes or so where I desperately tried to get my brain to cooperate while hearing words like “Circle of Power” and “Staff of the Ancients” tossed around in casual conversation as if this was intended to give me anything resembling motivation.

From here, you discover that this game has already committed the cardinal sin of bad gaming – it is not fun. The point of a game is to escape – to live another life, to have fun. SPARX repeatedly ensures that this is impossible, there is no escape. From the moment you’re dropped into the game, you are given an extremely linear path, but it’s worse than that – the path leads nowhere.

Let’s start with the gameplay. For a game about depression, I expect a tie-in with video games strongest philosophy, that failure is allowed, and can be recovered from – which is the core of treating depression in the first place. Instead, the game takes an outrageously patronizing approach I have not seen in any video game, ever.

You are not allowed to fail.

This is literally the worst sin I have seen in any game, of all time, period. No other game in my entire gaming history has ever denied me the chance to take a risk and pay whatever penalty there is for failure. Even games criticized for low difficulty usually minimize the penalty for failure, but never deny me the chance of it. In SPARX, the “enemies” are “gnats”, or bad feelings, which are hilariously non-threatening, and cannot harm you in the slightest – notably in contrast to actual depression, where harmful thoughts are actually dangerous.

Apart from being disingenuous, intellectually dishonest, and condescending – this is outright insane.

Depressed kids are not stupid. They are depressed.

Any child can see that this is not empowering – this is insulting. This is the equivalent of giving a 15 year old a bib, and telling them you’re so proud that they didn’t drop their peas. What’s infuriating is that this combination of games and psychology is so obvious and so powerful that it’s a wonder they went out of their way to deny kids this opportunity to fail and learn from failure after overcoming it – there is literally no better medium than video games to show that failure is not the end.

This is an exercise in self-indulgence by a design team that consists entirely of psychologists. There is no thought to the end-user – the people they are supposedly trying to reach. The game is clinically proven because it’s an extremely transparent attempt to transfer clinical techniques for psychiatry that work in a clinical setting to a game with no thought or effort, and then testing the game’s efficacy by forcing it upon a captive audience in a clinical setting. This doesn’t prove the game works, it proves that clinical techniques work in a clinical setting – an exercise in circular logic that would have made Aristotle proud. SPARX is not a game, it’s an insult to game designers, an insult to gamers, an insult to children, and worst of all, an insult to actually depressed people who need help.

.